A sermon from the Reverend Rachael Hayes

Our opening hymn, We Are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder, is a spiritual, composed by enslaved Africans in the United States. It is a song of perseverance, of struggling toward a goal, the goal ultimately being liberation.

The spiritual references one particular scene from the book of Genesis, in which Jacob has a dream of a ladder set upon the earth and reaching up to heaven, with angels going up and down the ladder, and then God blesses Jacob, confirms his birthright, and promises to be with him every step of the way.

Jacob does not actually try to climb the ladder, but the image of the ladder connecting heaven and earth endures.

Inspired by the same Jacob story as the spiritual but in a different take, St. Benedict wrote about a ladder of humility, in which the more humble a monk becomes, the closer he gets to God. St. Benedict’s 6th century humility, in which one monk won’t look into another’s eyes is maybe not so useful to us as we affirm each other’s dignity and worthiness, but the idea of a humility that works for 21st century Unitarian Universalists is long overdue.

How many of you have played Chutes and Ladders or Snakes and Ladders? I have to confess I mostly grew up with Candyland instead, which is a colors game instead of a numbers game, but it is also a game with a moving forward and being sent back mechanic, a game of pure chance and no strategy.

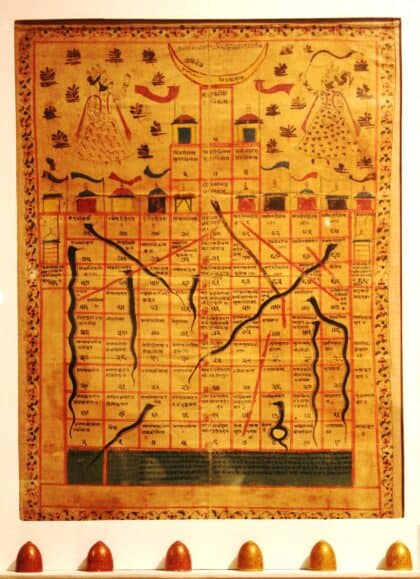

Snakes and Ladders came from an Indian game called Gyan Chauper. Versions of Gyan Chauper have been played for thousands of years in India. Dice games like Gyan Chauper are even mentioned in the Rigveda, which make them over three thousand years old. Many of the religions and dharma traditions with an origin or strong presence in India, including Hindu, Jain, Buddhist, and Muslim traditions, have used the game as not only entertainment but as a game for teaching morals and virtues specific to their belief systems.

I’m going to focus on the Jain version today, not because it’s the oldest or because it’s somehow better than the others, but simply because it’s the most uniform. Hindu, Buddhist, and Muslim versions of Gyan Chauper vary significantly even within each tradition, but the Jain version has the same virtues and vices and ladders and snakes in the same places throughout 2500 years of game play.

It’s a meditation rather than a race, and it’s a game not of strategy but of karma. The player advances toward the final square, which represents moksha, liberation from the cycles of rebirth and all of the suffering involved in living. The soul (and here I’m talking about the larger belief system, not simply game play) progresses and sometimes regresses on this path to liberation, hence the ladders and snakes in the game.

The virtues in the Jain version of Gyan Chauper are Faith, Reliability, Generosity, Knowledge, and Asceticism. These are the ladders that will get you to a positive rebirth. There are only five of them, so you have to be pretty lucky to hit one out of those 84 squares.

The vices or evils that will slide you down a snake to a negative rebirth are Disobedience, Vanity, Vulgarity, Theft, Lying, Drunkenness, Debt, Murder, Rage, Greed, Pride, and Lust. There are more than twice as many evils ready to knock you back than ladders to get you ahead, but maybe that balances against the slower incremental progress of regular movement.

Everything is moving all the time. Choosing not to play is actually choosing to stay where you are. We generate karma by trying to move forward, and it might get us a little bit further ahead or occasionally a lot, and sometimes in our trying to go forward we go backwards. Also, it may take millions of tries, but we will reach liberation. Maybe that’s why the first ladder is Faith.

So how did we get from this teaching tool of faith and morality to a mass-produced amusement for three- and four-year-olds? Colonialism, cultural appropriation, capitalism, the usual.

India was a British colony, and colonizers brought the game back to England, where it was altered to suit Victorian morals. The ladders stood on squares of penitence, kindness, pity, obedience, forgiveness, faith, truthfulness, and self-denial, which will bump you up 20 squares to finish the game immediately. The snakes’ heads rested on unpunctuality, covetousness, vanity, frivolity, dishonesty, quarrelsomeness, depravity, cruelty, slander, anger, selfishness, pride, and avarice. Did any of those chafe for anybody else? I feel like unpunctuality and quarrelsomeness alone would rule out a lot of us from ever reaching 100, to say nothing of how we rest with the virtues. These are the virtues and vices of the time, prioritizing souls that are industrious, agreeable, and selfless.

Eventually, the number of snakes and ladders became equal in the British version, reflecting that for every sin there is a chance at redemption. And then the virtues and vices were simply dropped as Victorian morality slid out of favor. In the twentieth century, after horrific wars and the end of the imperial age, the old morality no longer seemed to apply. So we get snakes and ladders that look like this one that we played today, simply snakes and ladders and counting.

What about Chutes and Ladders, the version I didn’t quite grow up with? Milton Bradley, and yes there really was a man named MIlton Bradley, produced a version that was explicitly for children. The illustrations on the board are of children, rather than adults, and you don’t have to read to understand what you’re playing. Instead of snakes, there are playground slides, because snakes are scary. And it actually looks like kid-sized karma rather than Victorian punishment and reward. The actions aren’t named but given cheerful pictures instead. Planting a garden leads up a ladder to a vase full of flowers. Rescuing a cat from a tree leads up a ladder to being friends with the cat. Climbing up high to sneak cookies that were put out of reach leads down a slide to both cookies and child falling to the kitchen floor. Writing on the wall with crayon slides you down to having to wash the crayon off the wall.

Chutes and Ladders never sat quite right with me, maybe because I was a stubborn kid (and still am deep inside) and thought that I was wiser than to eat a whole box of candy and make myself sick or to try to carry too many plates at once and wind up dropping them. I thought I should not face the consequences of these foolish actions that I only landed on by chance, not choice.

I wish I could tell my preschool self that I still make these mistakes regardless of my intentions, really, although it looks more like having one more cup of coffee than makes me feel good or transporting pottery haphazardly because I’m in a rush. It looks like all the times I should have taken a little more care. That’s the moral system of Chutes and Ladders, the Milton Bradley version: we all need to be a little more careful, intentional, and forward-thinking. Sometimes the thing that didn’t seem like a big deal at the time winds up having a big benefit or resulting in a big crash. And it’s okay, because you can still get to 100 even after being sent back to the beginning.

To deliver on my title, what would Chutes and Ladders for Universalists look like? And here I said Universalists, not Unitarians, because I think the old-school Unitarian version would look like having good character, maybe just an update of those Victorian morals we’ve already seen. Probably we would swap in “makes good coffee” and “thinks freely” and subtract a few of the morals that made us itch. My real question is what would Chutes and Ladders look like for Universalists? What does this game look like when heaven is not a goal, but a given? Does it happen on the board at all, or is this the board? Are we all walking it right now without knowing it?

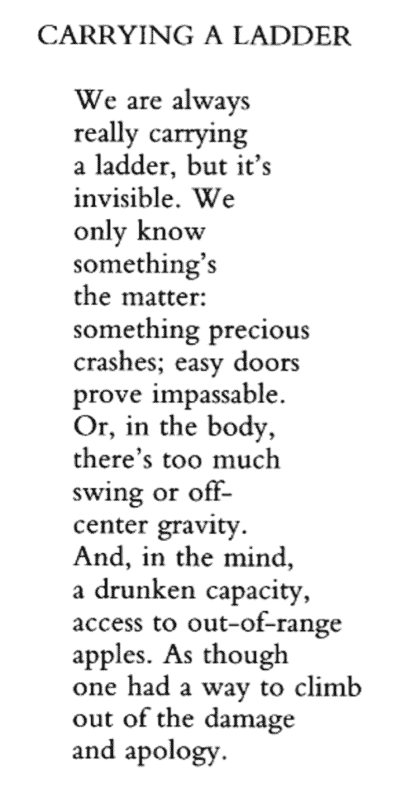

I have one more ladder for you, a poem, this one by Kay Ryan.

That poem says so much. It’s the lateral motion that’s hanging us up, not some game of up and down. It’s bumping into each other here, even with the best of intentions, not knowing where we went wrong, or at least not knowing until we’ve knocked our neighbor down. What if we could set the ladder down into the earth and aim it to heaven, to liberation, and work out some humility?

We’re not playing alone, of course, and it gets interesting when we put our ladders together. We can joust with them awkwardly, or we can prop our ladders against each other, even when we’re not sure where to aim. Two ladders can make a lean-to. Three ladders can make a scaffold. With enough of us and enough ingenuity, we can even figure out how to build ramps.

We can build more stable and inclusive structures of humility, where abundant welcome is the standard and collective liberation is the goal. I’m not talking about an afterlife heaven. As a 21st century Unitarian Universalist minister, afterlife heaven is not my concern. My concern is here and now.

Do all people have food, water, dignity, and love? As a Universalist, I’m saying that unless we’re all there together, it’s not actually heaven, or liberation, or beloved community.

So how are we going to build these scaffolds of humility, of freedom, of liberation? We take each other seriously. We listen to what our neighbors (and they are all neighbors) have to say, in their own words, in their truest emotions. We learn to see that we’re all in this thing together and until everyone’s free freedom doesn’t exist.

We build our scaffolds the best we can, trying to figure out the right place for each ladder, letting go of whose ladder is the longest, lightest, or most important. We will fall, we will disagree, and we’ll come back together in a new configuration. It’s a process. And when every need is met and every person is safe and loved, that is our heaven. The only real liberation is collective liberation. We only win together.